“Expressive, unapologetic, and ahead of her time in ecological and participative design” are the words that The Architectural Review uses to describe Minneta De Silva — widely considered the first female architect in Sri Lanka and one of the most important figures in South Asian modernist architecture.

Minneta De Silva was born in 1918 in Kandy, Sri Lanka, thirty years before the country gained independence from the British Empire. As the daughter of a reformist politician and suffragette who were family friends with the architectural legend Le Corbusier, De Silva grew up in a culturally privileged environment.

Even though her father didn’t support her desire to become an architect, she moved to Mumbai, and then London, where she attended the Architectural Association School of Architecture.

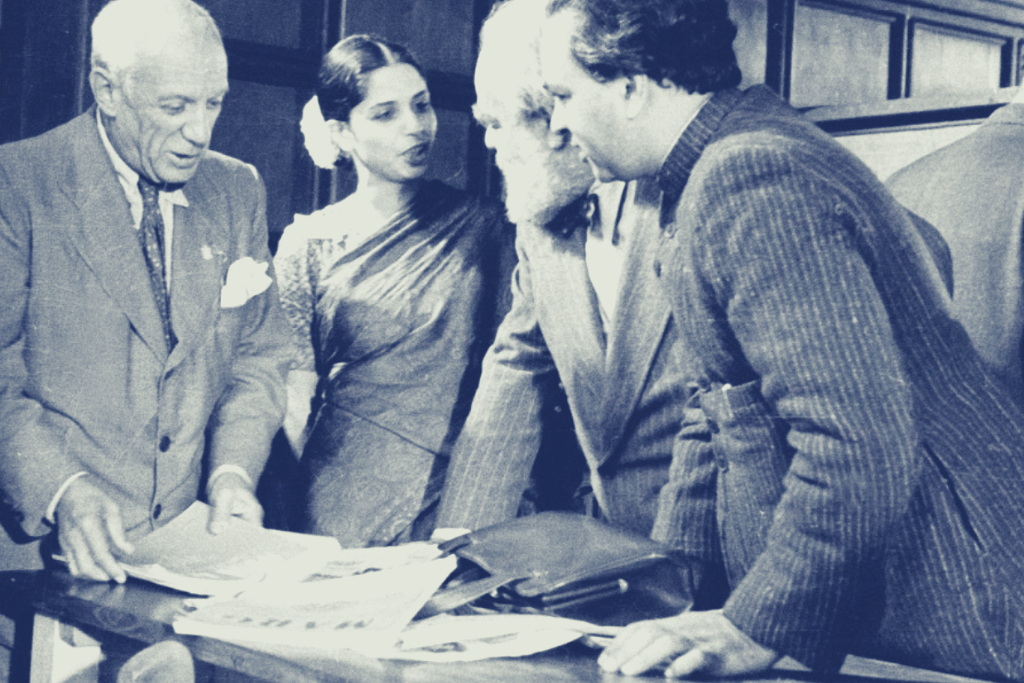

While living in post-war Europe, De Silva rubbed shoulders with the intelligentsia and some of the most prominent artists of the 20th century, including Picasso, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Laurence Olivier. She was the first Asian woman to become an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Nevertheless, according to The Guardian, she struggled to be taken seriously as an architect in Europe and was often considered an “exotic It girl”.

Becoming the Founding Mother of “Tropical Modernism”

In 1948, when Sri Lanka became independent, De Silva returned to her home country and opened her own architectural studio to help rebuild the post-colonial nation.

De Silva quickly established herself as a pioneer in introducing modernist architectural principles to Sri Lanka in the 1950s and 1960s. She believed that architecture should be adapted to local needs and conditions, rather than simply imitating Western styles. She designed a number of important buildings in Sri Lanka, including private homes, public buildings, and hotels.

De Silva’s style is currently known as “tropical modernism”, and she’s recognized as one of the principal architects behind this style, which responds to the unique environmental and climatic conditions of tropical regions.

Marking a Post-Colonial Nation’s Identity

Some of her most iconic designs include the Independence Memorial Hall, Kandalama Hotel, the Buddhist temple Shanthi Viharaya, Crestcat Boulevard, and Turret House.

These designs feature a combination of traditional Sri Lankan elements, such as courtyards and verandas, with modernist features like clean lines, flat roofs, and large windows.

De Silva’s buildings often have a sense of openness and fluidity, with spaces flowing seamlessly into one another. They typically feature open, airy spaces, with large windows and natural ventilation systems to help cool the interior spaces.

Decades before climate change and the negative environmental impact of construction materials became hot topics, De Silva designed ecologically-conscious buildings using local materials and traditional building techniques.

In addition to her architectural work, De Silva was a prominent advocate for the conservation of Sri Lanka’s architectural heritage, which was distorted by 300 years of colonialism. She was a founding member of the National Trust of Sri Lanka and worked tirelessly to preserve historic buildings and monuments throughout the country.

A Groundbreaking Approach to Participatory Architecture

Even though De Silva came from a privileged background, her approach to participatory architecture was ahead of her time. In the 1950s, she worked on a project to develop housing for public servants in her hometown of Kandy, which is the second-largest city in Sri Lanka.

This project was remarkable as De Silva involved future residents in the design process by consulting with them to understand their specific needs and preferences. Using this information, she created different types of housing units, and some of the residents even participated in building their own homes. This was a groundbreaking development in the field of architecture.

Tragic Late Years and Post-Humous Recognition

Even though De Silva redefined the postcolonial era in Sri Lanka and helped to construct a modern Sri Lankan identity, her career was marked by financial struggles and discrimination. She was excluded from professional networks and opportunities, and was often marginalized and overlooked by her male peers.

Furthermore, at a time when the profession of architecture was still in its infancy in Sri Lanka, De Silva’s work was also considered unconventional for its time and her designs were sometimes criticized for being too avant-garde.

When De Silva died alone in a hospital in her hometown Kandy at the age of 80, she was penniless and isolated, and many of her buildings fell into neglect and decay.

In recent years, however, there has been growing recognition of De Silva’s contributions to architecture and design, and she is now widely acknowledged as a pioneering figure in modernist architecture in Sri Lanka and as one of the first female architects from Asia to gain international acclaim.